Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his book Skin in the game, wrote about the difference between ensemble probability and time series probability. It sounds technical but it is a pretty intuitive concept when you take the time to think about it. The core concept is this – what usually happens with a thousand people doing something once is often very different from what happens when one person does the same thing a thousand times. I will explain this using the same thought experiment Taleb uses in his book.

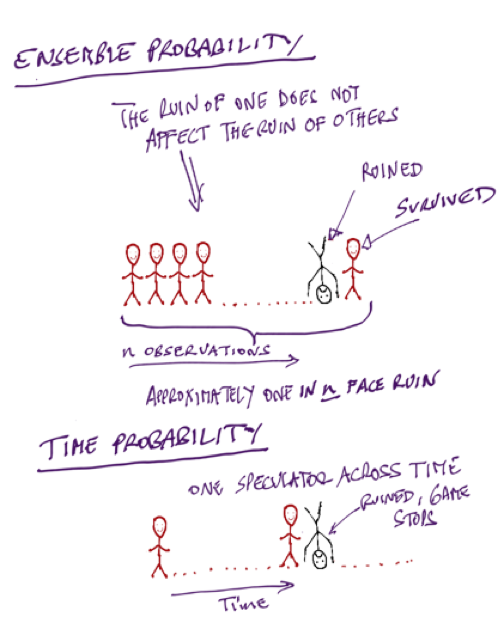

Imagine if you have a hundred people going to the casino to play a game that has a 50% chance of winning and 1% chance of losing everything. On an average, one person out of the hundred will go bust and the 50% of the people will win. In this scenario, the ‘ruin’ of one doesn’t affect others. Now imagine another scenario whose theoretical expected winnings are the same. One person goes to the casino 100 times. In one of the occasions he goes bust (let’s say it was the 28th time). Do you think there will be a 29th? Of course not, since he went bust there is no 29th time. The first scenario is called the ensemble probability (that of a collection) and the second one is called the time series probability (that of one person through time). This offers some basis for our behaviors that are driven by our survival instincts. This is in stark contrast to what behavioural scientists have called our inherent biases. Turns out they may not be biases at all, they may be rooted in our need for survival. Most of the research is done in ensemble cases while real life is lived in time series.

Imagine if you have a hundred people going to the casino to play a game that has a 50% chance of winning and 1% chance of losing everything. On an average, one person out of the hundred will go bust and the 50% of the people will win. In this scenario, the ‘ruin’ of one doesn’t affect others. Now imagine another scenario whose theoretical expected winnings are the same. One person goes to the casino 100 times. In one of the occasions he goes bust (let’s say it was the 28th time). Do you think there will be a 29th? Of course not, since he went bust there is no 29th time. The first scenario is called the ensemble probability (that of a collection) and the second one is called the time series probability (that of one person through time). This offers some basis for our behaviors that are driven by our survival instincts. This is in stark contrast to what behavioural scientists have called our inherent biases. Turns out they may not be biases at all, they may be rooted in our need for survival. Most of the research is done in ensemble cases while real life is lived in time series.

This is called ergodicity. When what happens with many is not a good indication of what might happen with you. Taleb says, as far as risk is concerned, this is the one concept we must all internalise. There are situations where the system is ergodic where what happens with many is representative of what happens with one. Imagine a 100 people tossing a coin once and one person tossing a coin 100 times. The expected number of heads remains the same. This is an ergodic scenario whereas our thought experiment is a non-ergodic scenario. The problem with the way we assess risks is that our actions in a non-ergodic scenario are mostly in line with an ergodic scenario. The classic case of this is how we as individuals expect to get market returns. Individuals go through ups and downs in life over time and their ability to ‘stick it out’ is dependent on them not completely decimating their savings (think the ruinous ‘going bust’ event in our thought experiment). A single event could be disastrous and this is where the idea of fragility comes from. For one to be able to enjoy market returns, one needs to first be able to survive the long run and continue to take risks. This also applies to funded startups (the go big or go home variety) who counter to this belief, go after one big idea with all their firepower. VCs that back these startups are however living very ergodic lives, making many bets at a time with no one singular bet having the power to cause their ruin.

An interesting analogue of this is how the behaviour of many users doing something once could be totally different from the behaviour of one user doing the same thing many times (think power users). This was brought up in the book Alchemy by Rory Sutherland in which he explains this with an example of commuters. He explains how the scenarios of one regular commuter who takes the same train everyday for 4 hours is so very different from other commuters who take the train once every week. Using averages to study behaviours is extremely problematic. Saving 1 hour on commute for 1000 people per week or 10 hours on commute for 100 people per week is not the same thing. The former seems like convenience but the second has potential to be life changing. Once you segment users in this way it becomes easy to understand what you want to focus on. Every time we use averages to understand something, we lose information.

The same goes for delivery fee for Amazon. Hundreds of people ordering something once per month may not mind paying the delivery fee for their orders but one person making a hundred orders per month (or any high reasonable number) will not be happy paying the delivery fee for each of their orders. Minor inconveniences incurred everyday with doing X, gnaw away a user’s experience until they can take no more and move on. This is not entirely obvious to product designers as they focus on averages and observe the behaviour of the larger number of users who do X with less frequency. It is important to segment users and observe their behaviours and not use a singular metric like mean, average or expectation, that tend to obfuscate information that may be the difference between creating something life changing for a set of users and something somewhat useful for a far larger group of people.

I run a startup called Harmonize. We are hiring and if you’re looking for an exciting startup journey, please write to jobs@harmonizehq.com. Apart from this blog, I tweet about startup life and practical wisdom in books.