Thinking fast and slow is one of my all-time favorite books. It epitomizes practical wisdom (tagline for this blog) and is loaded with warnings, pitfalls, and judgment fallacies. The core concept in the book is how our brain possesses two systems of thinking. System 1 and System 2. System 1 is fast, runs on biases and stereotypes. It craves coherence, stories, causal interpretations, and loves substituting tough questions with ones that are easier to answer. It is extremely emotional and easily manipulated. System 2 is lazy and hates being woken out of slumber. It understands mathematical and theoretical concepts and can help you work out problems with cold logic. In that sense System 1 isn’t a real system as much as it is a hijacker of decision making that gets in the way of logical thinking. The book is an absolute treasure trove and summarising it would mean creating multi-part blog posts, if not a short book in itself. In two posts, I will attempt to encapsulate some of the practical insights from the book that I have found to be useful in daily life and business. In this post, I look at 4 basic concepts that we should strive to keep in the back of our heads while making decisions.

UPDATE: Part 2 of this post it out too. In that post, I cover 3 more concepts that are super helpful in decision making in daily life.

Associations and substitutions

System 1 loves coherence and jumping the shotgun on decision making. It achieves this by substituting the question in front of us with another associated question, that is easier to answer. Imagine being asked what you consider a greater threat to our society – terrorism or traffic. Most of us would choose the former, when in fact terrorism is perhaps not even remotely responsible for as many deaths annually as traffic accidents. It is not the lack of knowledge about the actual numbers that prompted us to choose terrorism. When asked to take a few minutes to think about it, everyone will agree that the terrorism answer that popped into our head is not responsible for as many deaths. The reason we felt compelled to choose terrorism is we substituted the asked question (what is the bigger threat) with another question (between terrorism and traffic, which do you associate with a threat more easily). This is the availability fallacy. The terrorism answer was more “easily available” to us and System 1 jumped the gun. When making decisions, it is imperative to resist the temptation to substitute the real problem with another problem whose answer seems to lie in front of us.

Another interesting aspect of association is how easily we can be primed and influenced. In an interesting experiment done to understand how thinking about money affects us, college students were divided into groups and some of the groups were given fake currency notes. While they were being given these notes, a person walked in front of them and dropped some pencils on the floor. Students who belonged to groups that had been given the fake notes were found to pick up fewer pencils to help in comparison to those that were not given any fake money. Just thinking about money primes us to become more selfish and individualistic. Many more such experiments are described in the book and they all point to how easily we are influenced. There are events that speak directly to System 1 and affect our judgment. If you read headlines in the newspapers and find yourself attaching causality to them for events around you, remember it is your System 1 in action, that loves a good story.

Base rates

This one is a little mathematical and people not trained in statistics would probably not find this intuitive. Even those who have studied probability and statistics, often make incorrect decisions about things that are sometimes directly related to the concept of base rates. In simple terms, the base rate is the underlying chance of a certain event. It’s probably best to look at an example to see how base rate fallacy affects us.

Let’s say you are given a description of a college student that goes like – loves science fiction, enjoys doing Math problems and playing computer games, is introverted and likes to spend time in the library. Now take a moment to guess the major for this student. If you’re like most people, you probably thought of Compute Science since the description of the student reminds us of a typical nerd. You’ll most likely be wrong though and this is the base rate fallacy. In reality, only about 3% of the students enrolled in the colleges in the US are Computer Science students and the rest are divided into various disciplines like History, Arts, Biology, etc.

Even though the description of the person makes her highly likely, let’s say 4 times as likely to be comp sci than other disciplines, it is still extremely unlikely (~11%) that the student is actually from computer science because of the low base rate of computer science students.

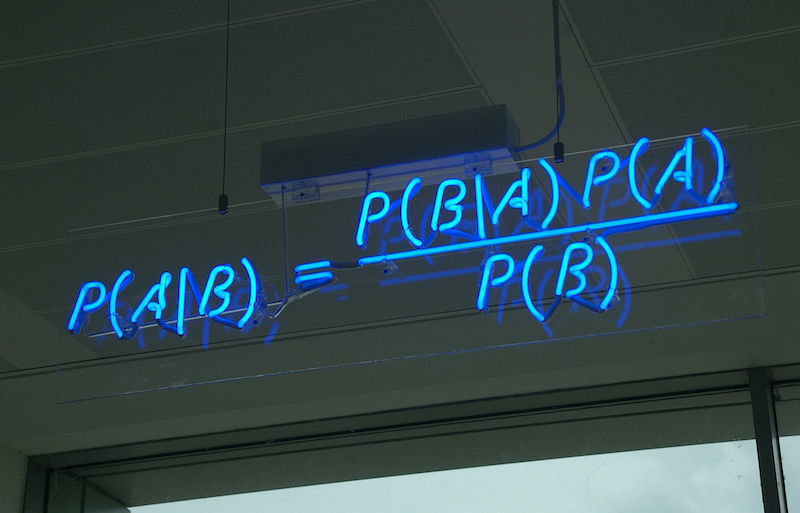

This is actually the Bayes’ theorem in action. Bayes’ theorem describes the probability of an event, based on prior knowledge of conditions that might be related to the event. For those interested in the underlying math, please refer to math.stackexchange answer to the problem of identifying the major of a student as discussed above. There is another interesting discussion of a cab involved in an accident based on the testimony of someone. Both these examples clarify how we just cannot rely on intuition on matters of chance and probability and that base rates are critical in arriving at a System 2 processed answer for such problems.

Regression to the mean

Random things have a way of regressing to the mean on their own, which is a fancy way of saying that if you observe outlier behaviors, it is likely that the subsequent events are going to normalize to the expected or average behavior. Basically, in the long run, things have a funny way of getting normalized. This is a stark contrast to the ‘hot hands’ idea. We are swayed by recent events and think that the trend will continue while in reality, things will always regress to the mean. A basketball player who seems to be in form and has made 10 shots in a trot is likely to miss the next one as his performance regresses to the mean. A stock that has been beating expectations and is well above its last few years’ values will likely come down and regress towards the mean.

A common mistake business managers make is observing short term effects of changes and jumping to conclusions. In reality some variations happen on their own. In time, these variations settle down and things regress to the mean. This is why you need control groups to understand the effect of your changes as some of the variations you observe are often a result of regression to the mean.

Outside vs Inside view

In a classic example of estimation, Kahneman explains how his team of experienced professors failed miserably at estimating the time it would take them to create a new coursebook on decision science. They estimated it would take them close to a year to finish the book. When Kahneman asked one of his colleagues to recollect the time it took for similar teams who had undertaken the creation of a coursebook before, he came back with 6 years as the typical time frame and that 40% of the teams ended up failing to even deliver the book. These numbers were much more pessimistic than the team had estimated for themselves. It is important to note that the team had with them the information they needed to make a realistic estimate but they just didn’t use it. This is the classic ‘what you see is all there is’ thinking that limits our opinions and decisions to things we are currently observing or thinking about. This is the inside view thinking fallacy. Once you start observing this, you will see it everywhere. When teams estimate how long it would take them to do something, when your colleagues look at the available data and make predictions about something, when CEOs get supremely optimistic about their newly taken decisions based on early signs, etc.

It is of the essence to take an outside view of things in all these matters. Outside view require one to observe things differently from an insider. Referring to the success rate and average times taken by teams to come up with a coursebook, in the above example is the way an outside view could have been taken. Seeking data that is not on the table, but available, is a simple way you can create an outside view. Always remember that what you see is not all there is. There is almost always something you are not trying to see.

In my next post, I will attempt to summarise 3 more concepts that I have found extremely useful and practical. These are – Loss aversion, that is perhaps the Kahneman and Tversky’s most consequential gift from prospect theory, Narrow vs Broad framing, which is useful in understanding how we assess risks and, finally, Experiential vs Remembering brain that helps you design better experiences.

I run a startup called Harmonize. We are hiring and if you’re looking for an exciting startup journey, please write to jobs@harmonizehq.com. Apart from this blog, I tweet about startup life and practical wisdom in books.