The book New Power, by Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms, explores the new power structures that are emerging in the world and how they are changing the way we live, work and play. The book is a great read for anyone who is interested in learning how we can leverage these changes to build movements and brands that matter. I’ll try and summarise my key takeaways from the book in this post.

New power models and new power values

The book talks about the new power models that are emerging in the world and how they are entirely different from old power models. The old power models rely on authority, commands and ownership while the new power models relies on values of openness, collaboration, transparency, and participation. The new power emerges from activities of the crowd. The MeToo movement, ISIS recruitment using social media, opatients using platforms like patientslikeme to discuss and learn from other patients on managing their similar diseases, etc, are all examples of new power models. A nice analogy to think about the old and new power models is look at the classic game Tetris in which you get tiles decided by the computer and then it overwhlems you eventually. Minecraft, on the other hand, is participatory. Other players create worlds for you and the game is about building on top of what others have created.

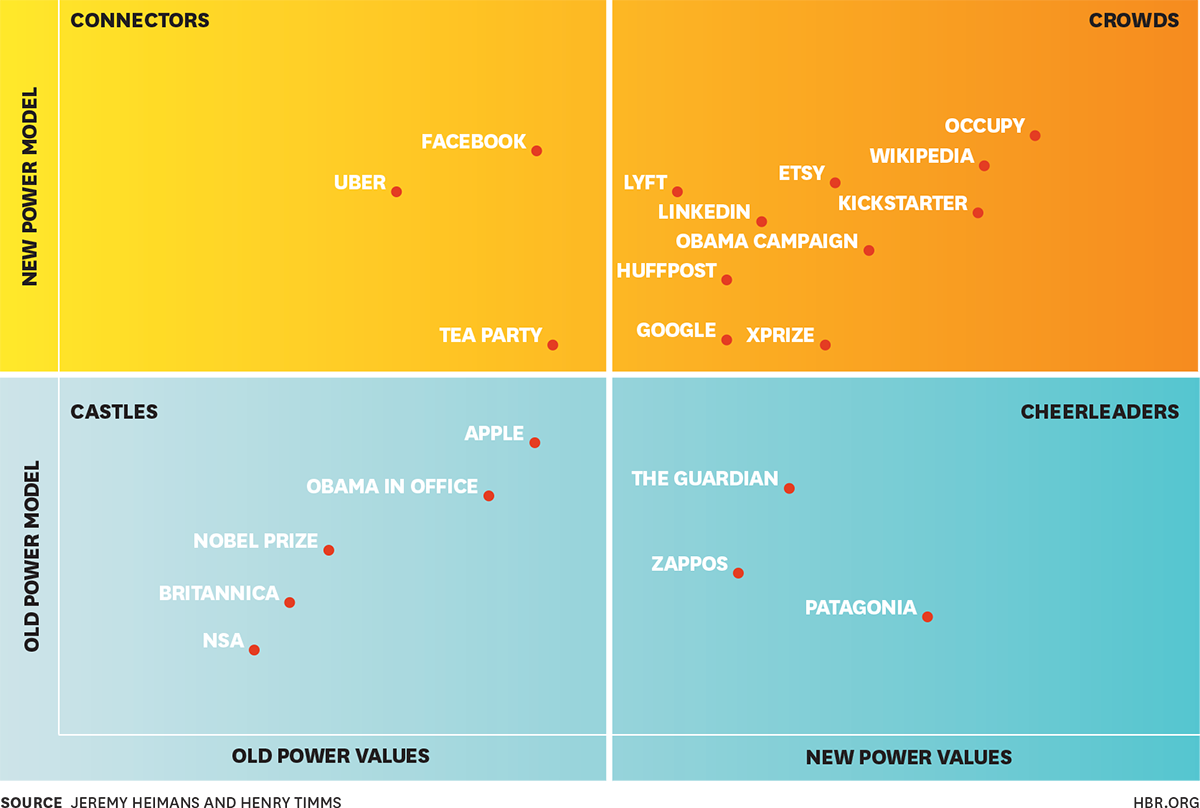

Old power values are managerism, institutionalism, top down governance, confidientiality, discretion, expertise, professionalism, loyalty, etc. New power values are informal networked governance, collaboration, crowd wisdom, short term conditional affiliation, part time participation, openness, radical transparency, etc. Here’s a neat graphic to think about how the old power models and values can mix and match in a 2x2 quadrant.

How ideas spread

There are some common aspects about ideas that spread (or movements that go viral). One example that is referenced in the book and that I also happen to recall from a few years ago was the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge. The challenge was to pour a bucket of ice water on your head and then nominate 3 other people to do the same. The challenge went viral and raised millions of dollars for ALS research. The book talks about the acronym ACE that spells out the three main aspects of the challenge that made it go viral.

- Action - they make us act in a certain way. The ALS ice bucket challenge, challenges us to pour ice water on your head. It is important to be less cynical about the actions, no matter how small they are. Gladwell defined “weak ties activism” or “clicktivism” as tiny irrelevant acts done on the internet that have weak or no correlation with the end objective but in reality, movements like blacklivesmatter, have shown that you can always move people from low participation to high participation. The challenge is to find the right action that will move people from low to high participation.

- Connected - promote peer connection with people who share common values. A key part of the ALS challenge was to nominate others to do the same. This kickstarts a network effect. Social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter are great at promoting connectedness. The book talks about how the ALS challenge was able to leverage the power of social media to spread the challenge virally.

- Extensible - can be altered or extended by people on their own while keeping the core idea safe. People innovated on their videos while still feeling they were joined to a common cause. This is based on the optimal distinctiveness theory. An ideal new power group should make its members feel like a part of a larger group and yet have potential for individual expression.

How to build new power communities

New power communities can be thought of as a triangle. This new power triangle is composed of the owners of the platform (and overarching rules), second are its participants (consumers and ordinary creators) and final side is the super participants, those who produce or consume a whole lot more than ordinary participants and keep the platform humming. Around this triangle are other factors like the following.

- How much power or agency to give to participants - The Occupy movement became so democratic that they lost steam as they kept debating within each other and the right way to come to decisions. While top down bureaucratic decisions also don’t work, the right balance is to give participants enough power to make decisions but not too much that they lose focus.

- Feedback loops from participants - what works, what doesn’t and to what extent.

- How to manage super participants - so that they keep producing and consuming more and more.

- Incentives and rewards - keep bringing the users back for more. Etsy’s 3.5% fees, Lyft returning the full commission post a driver crossing a weekly hour number, meetup upfront fees to host events, etc

- Recognition and statuses - karma points, blue tick, superadmins, etc. Perhaps this is linked to incentives but it is important to distinguish between the two. Recognition and status is about how you are perceived by others. Incentives are about how you are rewarded by the platform.

- Participation premium - think of it like this equation something you’re selling + higher purpose * participation. Decouples the value of the product from the price paid by the participants. The example of Starcitizens comes to mind. Starcitizens are a community formed around a space travel game that is in design. It’s members have already enjoyed benefits of a community of a niche shared interest even before the game is launched. Xiaomi also first created community of cellphone design enthusiasts that leverages the ikea effect as participants pay more for stuff for which they played a role to build.

I run a startup called Harmonize. We are hiring and if you’re looking for an exciting startup journey, please write to jobs@harmonizehq.com. Apart from this blog, I tweetabout startup life and practical wisdom in books.