In his book How to be perfect, Michael Shur, the writer behind shows like The office, Brooklyn Nine-Nine and The Good Place, introduces us to important moral philosophical concepts that help us distinguish right from wrong. Think of it as a 101 moral philosophy course by a really witty and humorous professor.

The book is his condensed understanding of the key moral ideas that have shaped the modern world, ranging from Aristotle’s Golden mean to Kantian Deontology to Bentham’s Utilitarianism to Sartre’s Existentialism. This book will absolutely make you sound smart in a party if you’re into that sort of thing. In this post, I try to summarise the key moral philosophical ideas described in the book.

Aristotle’s Golden Mean

Aristotle’s Golden mean can be summarised in one line as “nothing in excess”. According to Aristotle, we all have capacities for acquiring virtues. The author calls this “being born with a good starter kit”. We need nature, habit and teachings to develop our sense that comes not by nature, but through habituation i.e. practice. It’s like learning to bagpipe (we may have aptitude for it but we get better by doing it under instruction from a good teacher). The Golden mean is the perfectly balanced amount of quality (deficiency v excess). It’s a Goldilocks zone of virtue. The idea is to modulate ones inclinations of our starter kits and practice striking the balance. According to this philosophy most of what is wrong with the world can be described in terms of being excess of something or dearth of something else.

Utilitarianism

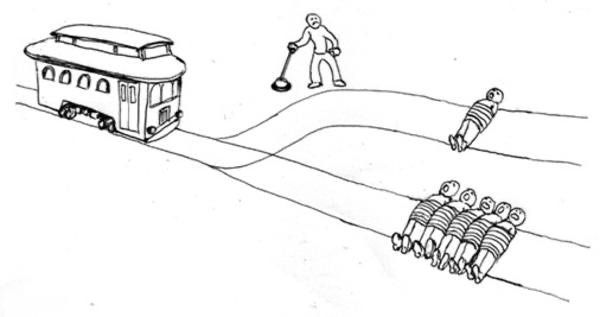

Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarianism is the idea that the right thing to do is the thing that maximises the happiness of the most people. This is a simple mathematical idea that upon even the slight deeper inspection starts to show cracks. According to utilatarianism (or consequentialism as it is often called) it would be absolutely ok to kill one person to save two. The famous trolley problem finds a simple solution according to this philosophy. If you’re on a trolley track and you see a trolley coming towards five people, you can either pull a lever and divert the trolley to a single person or you can do nothing and let the trolley kill five people. According to utilitarianism, you should pull the lever because it maximises the happiness of the most people. This is a very simplistic formula and it doesn’t take into account the fact that the person you’re killing is a person too.

J S Mills improved upon this basic idea by adding another condition which prevents us from harming other people. The new and improved utilitarianism thus becomes, we should only do things that maximise the happiness of the most people as long as it doesn’t harm anyone else. It is still a very simplistic formula but at least it doesn’t allow us to kill someone to save others.

Kantian Deontology

According to Kantian Deontology, the right thing to do is the thing that is right in itself, regardless of the consequences. Immanuel Kant forces us to derive universal maxims and ask ourselves if we would want everyone to follow them so things like lying, cheating or stealing are wrong. If you’re doing something that you would not want everyone else in the world to do, then it’s probably not the right thing to do. This idea is called the Categorical Imperative. This is based on the underlying concept that humans are inherently better and they must do the moral thing out of a duty and not a need. Kantian philosophy is rooted in the notion of humans being better than the rest of nature.

There is an adapted version of the categorical imperative that restricts us from using people as means to and end. This is quite a handy maxim and helps us justify not killing or hurting a person to any goal that we may have.

Scanlon’s Contractualism

As you can imagine, contemplating if what we’re doing can be treated of as a valid universal maxim is a very difficult and cumbersome thing to do. A somewhat summarised version of this is the theory of Contractualism by T M Scanlon. It suggests that there are simple baseline levels of behavior that we all agree to be reasonable (don’t steal, don’t drive in the emergency lane, etc). Just imagine what can be considered as a reasonable expectation from others and then ask yourself if what you’re doing is something that violates that.

There is a South African philosophy called Ubuntu that loosely translates to living through each other. It can be thought of as “I am, because we are” and it supercharges Scanlon’s contractualism. It says not only do we owe reasonable behavior to each other, we exist through each other. Nelson Mandela once explained Ubuntu as enriching oneself to enrich the community (as opposed to at the expense of).

William James’ Pragmatism

Pragmatism dictates that the right thing to do is the thing that works. It’s a very pragmatic approach to morality that focusses on the end and doesn’t worry too much about the way it is achieved. Pragmatism asks us to play referees and blow the whistle if we see some practical differences in the way ends are met. For example if Jeffrey Epstein were to donate to charity to whitewash his name, it would be different from any other person doing it for a little ego massage. While the Kantian would reject both, a pragmatist would allow the latter but reject the former.

Sartre’s Existentialism

Sartre and Camus were two famous French existentialist philosophers of the post war times. Sartre’s Existentialism describes that there is no structure or meaning before we are born. After we materialise it is upto us to define ourselves with our actions. It is thought to have given rise to these two somewhat contradictory ideas:

- There is no God and all we have are ourselves to hold ourselves accountable

- We humans should hold ourselves accountable to a model behavior without guidance from any other theory

Camus explains that humans desire meaning from the universe which it denies. We’re a lot of nothingness and all life is made absurd by our desire to get meaning from the world. Camus says Sisyphus is actually happy as he doesn’t need to find meaning in his rock task cause he knows it is a punishment in the form of a pointless task.

I run a startup called Harmonize. We are hiring and if you’re looking for an exciting startup journey, please write to jobs@harmonizehq.com. Apart from this blog, I tweetabout startup life and practical wisdom in books.