This is the part two of a two part series on lessons from Amy Edmondson’s book The Right Kind of Wrong. In the first part, I talked about the different kinds of failures and why one is better than the other. In this post, I will talk about how to create a team that encourages good failures.

Psychological safety

Popularised by Google’s project Aristotle which was done to study commonalities between successful teams, psychological safety came through as the key trait. A safe environment for people to bring their whole selves to work, take risks and speak their minds, makes for effective teams and organisations.

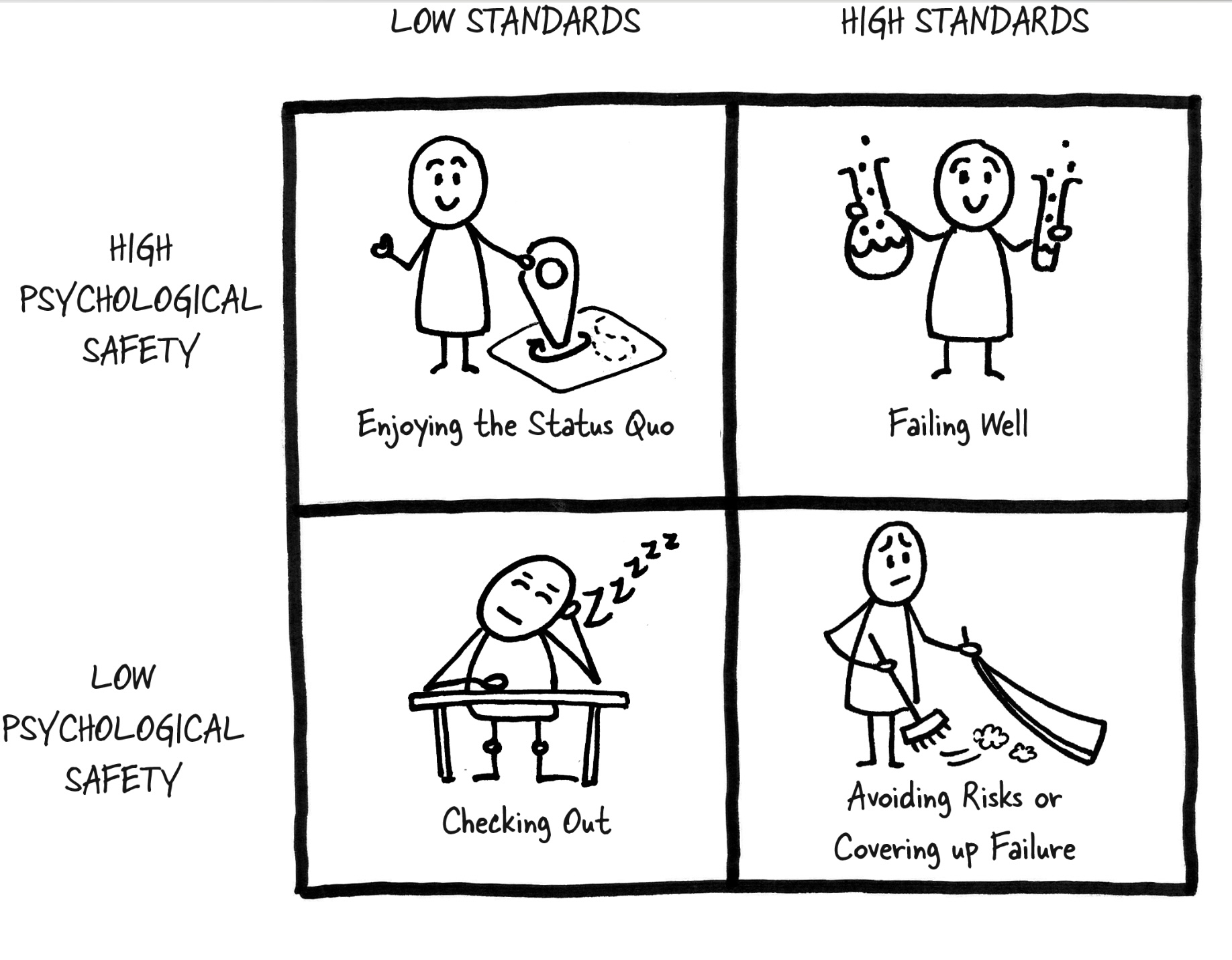

Psychological Safety is also linked to failing well. If your team or organisation has psychological safety and high standards then people will strive to fail well but with low standards, people will enjoy the status quo. See the chart below to see how these two factors can play out.

To understand how this works, we need to look at the three main barriers to failing well.

- We are averse to failing - by learning to reframe to build healthy attributions as to why we failed, we can become more open to learning from failing. Being able to reframe a situation is a key skill to have and can be learnt. In Clearer Closer Better, Emily Balcetis discussed this at length.

- We are confused whether the failure was a bad one or a smart one - need a framework for spotting failure types. We discussed this in the first part. In short, intelligent or smart failures happen in a new space, has low risk or costs and is a part of a meaningful opportunity.

- Afraid of failing - a psychologically safe space encourages experimentation which by definition leads to failures.

A psychologically safe space is a supportive environment that enables people to experiment, fail, talk about the failure and then iterate on this process. This is the key to failing well.

Capabilities to Deal with Failure

An ideal intelligent failure is about failing in a new space with low risk. These three capabilities help one assess various situations and contexts and build the necessary awareness to ensure that the failure is an intelligent one.

Contextual Awareness

The key point about failures is understanding how much is known and what is at stake. The goal is to pause and assess the situation and the level of uncertainty, removing unnecessary anxiety associated with most situations. If the situation operates in an unknown space, then the failure is almost guaranteed, and it’s not even really a failure but the gaining of new knowledge.

Variability and a lack of routine can stump individuals and make a situation appear too consistent, which, in turn, can lead to pressure-free operations. If we regularly operate in a routine and consistent context, we can become overconfident. When such a person finds themselves in a context with a significant amount of variability, basic failures can happen.

When the stakes are high, you want to move carefully and follow protocols. In low-stake situations, you can move quickly, failing quickly with low vigilance. The important thing is to develop the ability to understand the context of the situation and then act accordingly.

Situational Awareness

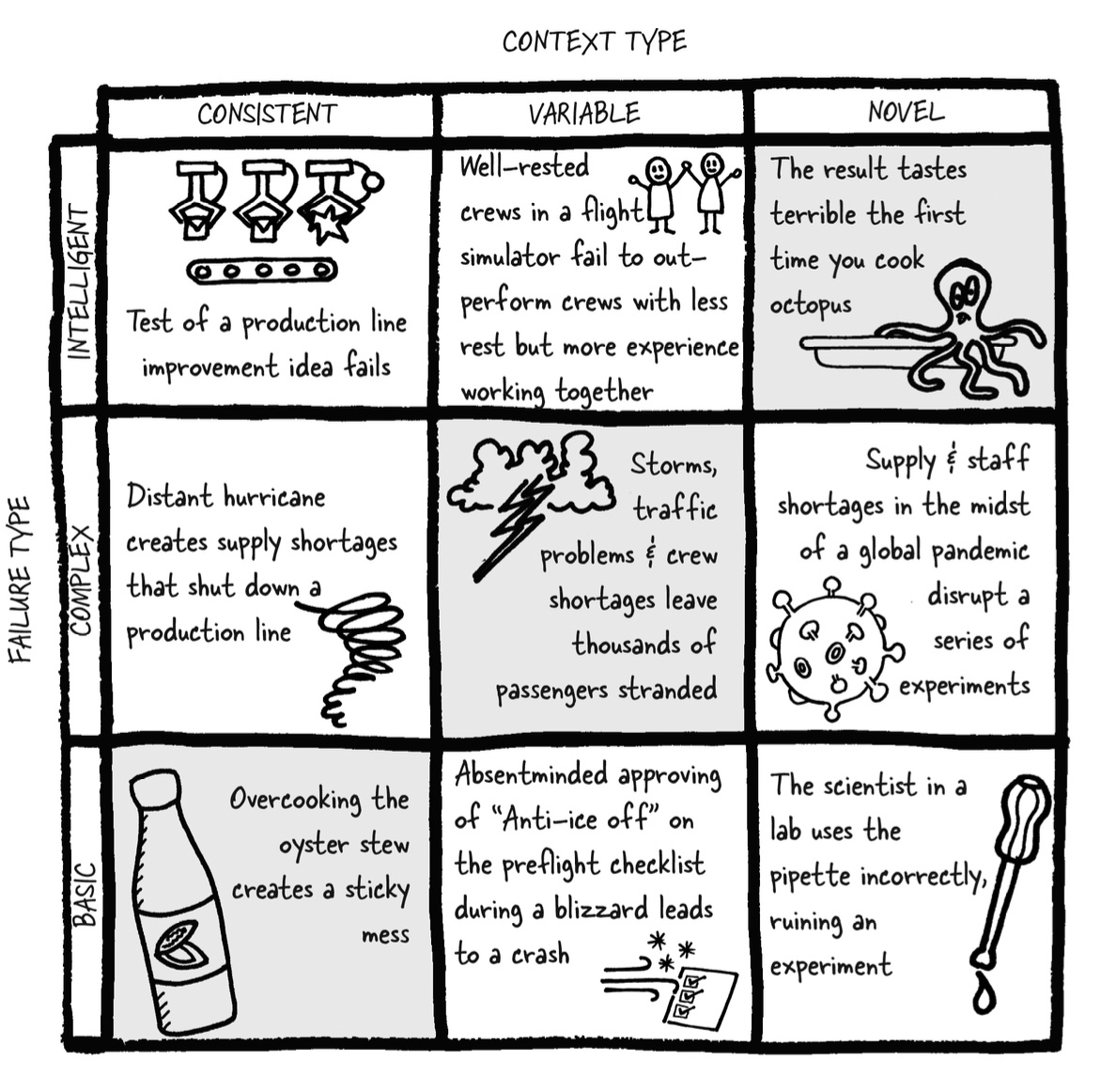

Naive realism is a type of bias that stems from our belief that we see reality itself and not a version of reality. This bias makes us overconfident because of our experience or background and makes us underestimate variability, leading to avoidable mistakes and failures. Basic failures are common in consistent settings, intelligent failures in novel ones, while complex failures take place due to variable settings.

Mixing three types of contexts - consistent, variable, and novel with the three failure types - basic, complex, and intelligent, we get nine combinations of failures occurring in different situations, as shown below:

System Awareness

Developing a systems thinking approach helps us spot interconnected elements and avoid complex failures. Systems thinking allows us to see beyond isolated components to the intricate web of interconnected elements. It teaches us to recognize how elements work together, often with feedback loops, forming a cohesive system. This holistic view is essential for anticipating potential failures and finding sustainable solutions.

A fascinating example of systems thinking in action is the beer game study. Here, participants are divided into four groups – retailers, wholesalers, distributors, and a factory. The challenge is to manage beer inventory based on fluctuating consumer demands. It’s an eye-opener on how each decision, though rational in isolation, can lead to unintended consequences for the entire system. This simulation vividly illustrates the swings in demand and supply, emphasizing the need for a broader perspective in decision-making.

Systems thinking also sheds light on common pitfalls in managing complex systems:

Downstream Errors: Often, we don’t foresee the future implications of our decisions. Systems thinking encourages us to anticipate and plan for these potential errors.

Quick Fixes vs. Sustainable Solutions: The temptation to implement quick fixes can be counterproductive. By understanding the system as a whole, we can devise more effective, long-term solutions.

Redrawing the Boundaries: Reframing a situation by thinking about boundaries differently can help achieve more impactful interventions. For example, consider the case of a children’s football match. Would you think about it differently if, instead of considering your own feelings, you also considered the feelings of all the other parents involved? What new things would then become more acceptable or unacceptable to you?

Practices to build a relationship with failure

Follow these three simple practices to develop a healthy relationship with failure

- Persistence - develop the muscle to persist for longer durations. Grit plays a large role in failing well. It is the ability to persist in the face of adversity that helps one to approach the same problem from different angles and eventually succeed.

- Accountability - taking the responsibility of your role in the failure allows one to go through the pain of looking back and learning from the failure. On the other hand not listening, not being clear or simply not doing something well enough can lead to basic failures or complex failures that could have been avoided.

- Apologies - an effective apology improves relationships and future chance of doing better together as a team. A good apology has three parts - an expression of regret, an explanation of what went wrong and an offer of repair. A good apology is not about making excuses or blaming others but rather about taking responsibility and making amends.

I run a startup called Harmonize. We are hiring and if you’re looking for an exciting startup journey, please write to jobs@harmonizehq.com. Apart from this blog, I tweet about startup life and practical wisdom in books.